On June 25, 2014, the Supreme Court in a unanimous decision, ruled that police may not, without a search warrant, search digital information on a cell phone seized from an individual who has been arrested. The Court settled two conflicting cases Riley v. California and United States v. Wurie. In the Riley case, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals found that the search of the cell phone was permissible as a valid search incident to arrest, as it was “immediately associated” with his “person” when he was arrested. Because the cell phone was on Riley’s person when he was arrested, the police were justified in performing a full search incident to his arrest. In the Wurie case the First Circuit Court of Appeals held that warrantless cell phone data searches are unlawful under the search incident to arrest exception. It noted that the government failed to demonstrate that a cell phone search under such circumstances was necessary to promote officer safety or prevent the destruction of evidence. The fact that the officers had Wurie’s keys and his cell phone which they used to locate and enter his apartment without a warrant to “freeze” it while they obtained a search warrant was unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court in reviewing both cases indicated that the search incident to arrest exception to the Fourth amendment warrant requirement is inaccurate because warrantless searches incident to arrest occur with far greater frequency than searches conducted pursuant to a warrant. The opinion then laid out a discussion of the handful of Supreme Court precedent in the search incident to arrest area, beginning with the seminal case limiting the scope of a search incident to arrest, Chimel v. California, 395 U.S. 752 (1969) (disallowing the search of an arrestee’s home even where he is arrested therein), and United States v. Robinson, 414 U.S. 218 (1973) (permitting the search of a cigarette pack found on the arrestee’s person at the time of arrest). The Supreme Court applied a balancing test for warrantless searches, which compares the degree to which a warrantless search intrudes upon an individual’s privacy versus the degree to which the warrantless search is needed for the promotion of legitimate governmental interests, the opinion discussed the difference between the search of digital information contained in a cell phone and the search of physical objects like the cigarette pack in the Robinson case. The Court then discussed the two rationales weighing in favor of permitting a search incident to arrest established in the Chimel case and followed in the Wurie case, to promote officer safety or prevent the destruction of evidence. As for the need to uncover and disarm weapons from a defendant, the court held that law enforcement officers are still free to search the physical aspects of a cell phone to make sure there are no physical threats. However, the digital information contained with a cell phone poses no physical danger to a police officer. Then, as for the interest of preventing the destruction of evidence, the Court held that there is not much of a threat of this, and that there are reasonable, cost-effective options available to law enforcement which can ensure that data will not be lost if they thereafter choose to apply for a search warrant.

Contact Our Office

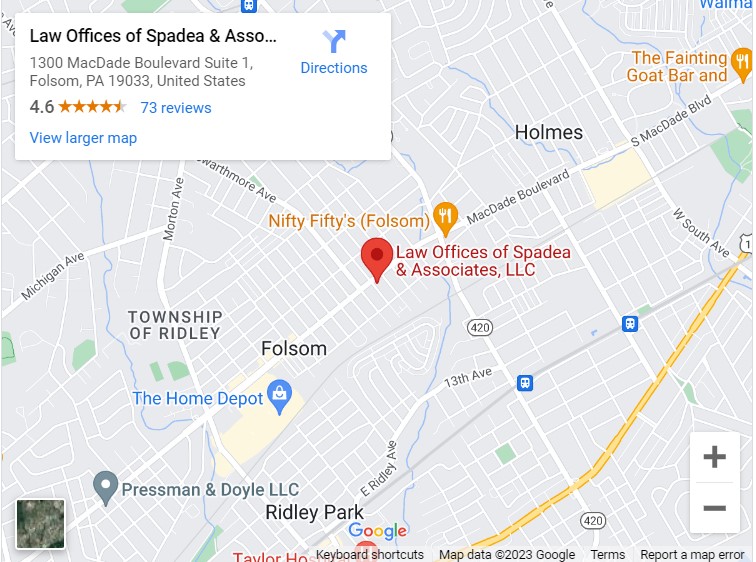

If you are ever arrested or have your cell phone confiscated by police call Gregory J. Spadea of Spadea & Associates, LLC at 610-521-0604, located in Folsom, Pennsylvania.