How a Pennsylvania Family Court Determines Custody

No issue is more important when parents separate than the custody and future of their children. Answering this question is also one of the most difficult and unwelcome decisions that a judge must make. The process is complex, the results uncertain, and often expensive. Multiple people, who are strangers to you, your spouse, and your children, can be involved, people such as court-appointed custody masters, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and ultimately judges. All of them are looking out for the “best interests of the child.” None of them really know what that means.

To guide them all, Pennsylvania law requires that they answer a staggering sixteen invasive and uncomfortable questions to help the Court determine the following:

- Which parent is more likely to help foster contact and the relationship between the child and the other parent;

- Which parent is more likely to have a loving and stable relationship with the child; and

- Which party is more likely to take care of the child’s daily physical, emotional, and educational needs.

- Which parent takes care of the child’s basic needs;

- The availability of extended family;

- The accessibility of child-care; and

- The distance between the parents’ homes.

The Courts will even assess your own mental, emotional, and physical health. If your child is old enough and mature enough, the Courts will take your child’s preferences into account. However, your child’s preferences are not supposed to be the controlling factor.

Custody masters and judges typically use these factors like a score card, ticking off boxes in favor of one parent or another. Then, they add up the score and make their decision. They do not simply give each factor the same weight and declare a winner, however. Moreover, the Courts may not make custody decisions based on gender. They do, as a practical matter, though, still prefer mothers of young children over fathers. It is hard for father’s to overcome this preferential treatment of mothers. Some factors are more important than others. Some facts lean more heavily in favor of one parent or the other. Even with the factors, fundamentally no judge or custody master looks at the same facts in the same way. That is what makes it so difficult for parents and their attorneys to predict how a judge will decide a custody request.

Even if different judges may assess the factors the same way, at the end of the process they still must decide how to actually divide the custodial time. That decision will determine who gets weekdays, who gets weekends, who gets holidays and vacations, which school will they attend, and even possibly who drops the children off and picks them up. While there are some basic schedules used, different judges will establish different schedules.

For parents, who must leave their children’s home on short notice and do not have a second home for themselves and their children, securing custody of their children can be very hard financially. Courts will limit the out-of-home parent’s time, including overnights with their children, if that parent does not have enough bedrooms and beds for their children. But, setting up a second home on short notice is expensive and time-consuming, especially when, as is so often the case, displaced parents generally do not have much money for their own housing after paying child or spousal support.

The amount of your custody time will also affect the amount of child support payments. To make matters more challenging, keeping up a good relationship with your child is particularly important just after separating for securing a good, long-term future with your child. So, displaced parents should try to make a suitable home for themselves and their children as soon as possible.

All of these considerations make the fight to protect your time and relationship with your children the most difficult and important aspect family separation.

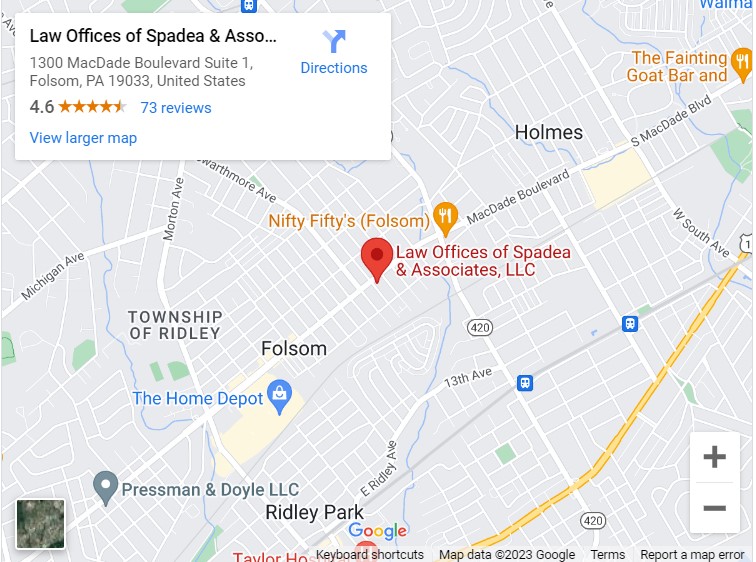

If you need help establishing your right to custodial time with your children or have questions about child custody law in Pennsylvania, please contact Shintia Riva At the Law Offices of Spadea & Associates, LLC for free 20-minute consultation.